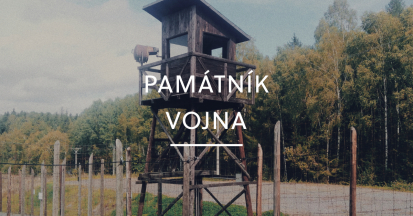

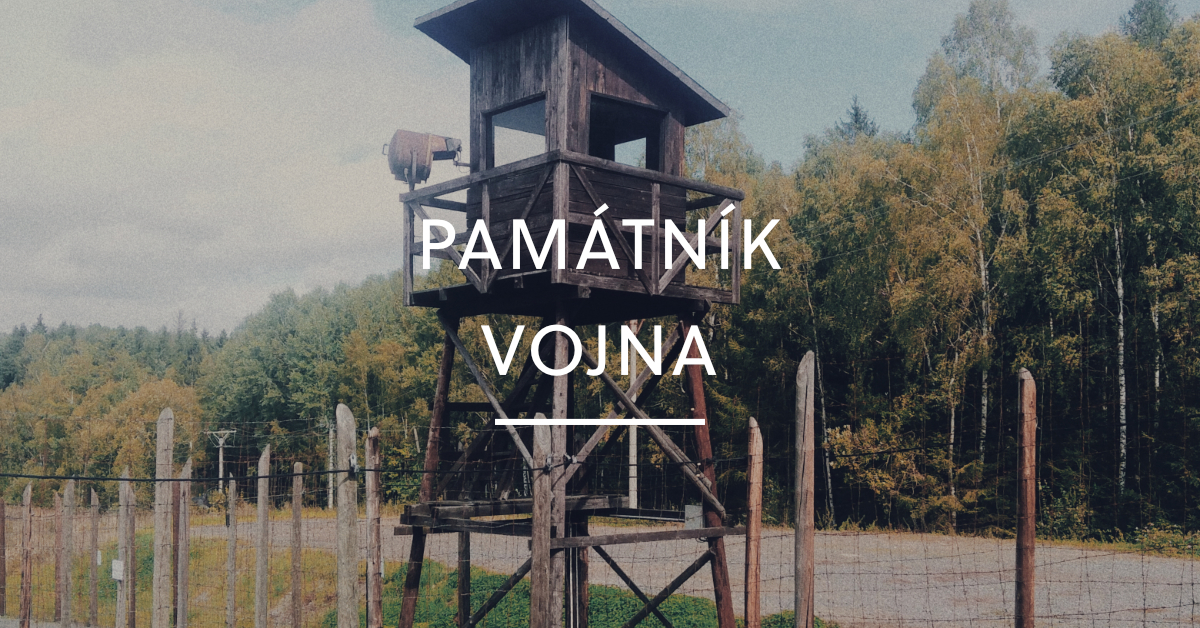

War Memorial

You don't have to go far to see for yourself how horribly some regimes and historical eras have treated their own and foreign citizens.

Five kilometres southeast of Příbram is the only partially preserved communist camp in the Czech Republic.

| In the middle of the forests southeast of Příbram, in a place known for its iron, silver and uranium ore, a labour camp was built by German prisoners of war in 1947-1949. It was named after the nearby hill Vojna, at the foot of which it is located. Similar facilities also existed in the Jáchymov and Slavkov regions in connection with the extraction of the aforementioned strategic uranium ore. At the turn of the 1940s and 1950s, German prisoners of war had to be removed to Germany in accordance with international treaties. There was a problem of how to fill the vacancies. As a result of the communist takeover in February 1948 and the subsequent socio-legal developments, the state leadership of the time decided to use for these purposes a considerable amount of labour from among the so-called forced labour camp inmates, who began to fill the former prisoner of war labour camp at Vojna from mid-1949. |

| The POW labour camp at Vojna was filled with people who had been interned without trial for political reasons, illegally. Gradually, the largest forced labour camp for uranium mining in Czechoslovakia was established there. In March 1950 it had 530 inmates, a year later it had 761. They were used to perform tasks in the mining activities and to ensure the running of the camp, including its expansion. From May 1950, a separate company of a special unit of the National Security Corps (SNB) called Crane III guarded the premises. |

| A citizen did not have to have committed any crime to get away from the forced labour camp. A mere suspicion that he might commit the act was enough, and he was sent to the camp as a precaution. "A person between the ages of 18 and 60 could be assigned to a forced labour camp, with a few exceptions, without a proper trial, for a period of three months to two years, by decision of NV officials, members of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, who settled scores not only with their political opponents," writes František Bártík in his book Camp War in the Light of the Memories of Former Prisoners. "The significance of the camps lay primarily in the isolation of the enemies of the establishment at the time, who were to be re-educated through work, for which they were to receive a proper wage, and through political training into valid fellow citizens building a communist society." |

| "I was first deployed as a scavenger, then as a locksmith at the ventilation system. The working hours were 8 hours each time in 3 shifts. The standards were very high and for the most part could not be met. Our standard was raised by the Russian instructor compared to that of civilian workers. The treatment was partly very brutal, because after 8 hours of work on the shaft there were always 2 hours of additional work during the day in the camp," recalls one of the prisoners at the time in František Bartík's book. |

| In 1951, with the reorganisation of the forced labour camp Vojna, it was transformed into the Corrective Labour Camp Vojna, which was a prison facility. The most dangerous, especially state security criminals" were placed in Vojna, i.e. people from the ranks of democracy supporters who had been sentenced more than once in fabricated trials to 10 years or more, most often for treason, attempted treason, aiding and abetting treason, espionage, attempted illegal departure from the republic, and subversion of the people's democratic establishment. Along with them, criminal and retributive prisoners and those convicted of the so-called black market also served their sentences here. |

| The desire for freedom led many of the prisoners to organise escape attempts, mostly unsuccessful. There were also protests, for example the famous hunger strike at Camp Vojna in July 1955, which resulted in 11 convictions for treason and sedition, with sentences ranging from 4 to 12 years. The crown witness in the investigation of this case was the retributive prisoner Pampl, a member of the Nazi Sicherheitsdienst during the occupation, who revealed the organizers of the action from among the political prisoners to the state security. After five years, he was released for exemplary behaviour, while the last of the initiators of the hunger strike was only released on amnesty in 1968. |

| In the long line of names of political prisoners, the ones that catch the eye are those belonging to people who have made a significant contribution to our state in previous historical developments. Post-war Czechoslovakia "rewarded" them with forced labour in uranium mining behind barbed wire. Among them were well-known scientists, artists, clergymen, politicians, sportsmen (hockey players, world champions of 1947 and 1949). A particularly bitter irony of fate is the fact that many heroes of the anti-fascist resistance appeared here, along with their recent adversaries, Hitler's war criminals, members of the former Nazi apparatus, collaborators and traitors, who in many cases were deliberately placed by the camp authorities in the places of execution among the punished. And with these prisoners, completely innocent people had to suffer for many years. In connection with the decline of prisoners after the amnesty in 1960 and in view of other operational reasons, the Vojna camp was closed down on 1 June 1961. The remaining prisoners were partly transferred to the nearby NPT Bytíz. This prison facility still operates today, but under different conditions. The Vojna site was used by the army between 1961 and 2000. In January 2001, it was declared a cultural monument and in 2005, after a difficult reconstruction, it was opened to the public. |

Other articles: